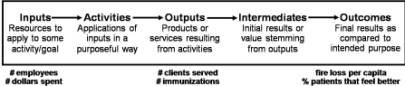

While it dates back to the 1970s, the Logic Model gained prominence in the 1990s largely in response to the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA). The Logic Model provides organizations with a framework for understanding the relation between resources or inputs (what an organization invests); activities or outputs (what an organization gets done); and outcomes or impacts (what results or benefits happen as a consequence):

- Inputs or resources that go into a program may include time, people (staff, volunteers), money, materials, equipment, partnerships, research base, and technology, among other things.

- Outputs are activities conducted or products created that reach targeted participants/populations. Outputs are “what we do” or “what we offer” and may include workshops, delivery of services, conferences, community surveys, facilitation, in-home counseling, etc. Outputs lead to outcomes.

- Outcomes, a central concept within logic models, are benefits that result. Examples include changes in knowledge, skill development, behavior, capacities, decision-making, and policy development. Outcomes occur along a path from shorter-term achievements to medium-term and longer-term achievements. They may be positive, negative, neutral, intended, or unintended.

Many variations and types of the Logic Model exist but the essential element within all of them is the importance of understanding and communicating outcomes and how the organization is doing in achieving them. The Logic Model has become a widely accepted management tool in the public and nonprofit sectors. For example, California’s Strategic Growth Plan states (emphasis added):

Prior to any funding being expended from existing or future bonds, the responsible state agencies must develop performance and outcome measures for each program and project that would be funded from the bonds. Regular audits will be conducted to ensure that funds are being allocated according to those outcome criteria and that the implemented programs and projects did in fact achieve the intended outcomes. It is imperative that the public be able to access this information.

Organizations might use dashboard measures to track the resources that they consume and the services they produce but the key performance indicators on their scorecards should be focused on the outcomes that they are trying to achieve. Furthermore, high-performing organizations link pay to performance by incorporating these outcome KPIs into personal MBOs, rather than input or output measures. Essentially, we incent people for what we want them to accomplish not for what they do.

This is a canonical activity-based costing model!

I do understand that it makes a lot of sense judging organizations, projects with purely outcome-oriented KPIs. I don’t think that it is the best idea to assess individual performance the same way. Assume person A is a great expert at topic T in programming language L, but a beginner in Topic U in programming language M. Now if management decides that T is out and U is important and U happens to be written in M, and thus in the next year poor A has to work on U instead of T and in M instead of L, the final, measurable outcome of his work is bound to be much lower than if management would have prioritized differently (from my experience I’m talking about factors above 10 here).

It is reasonable of management to decide to go for U instead of T, because it might not make sense to invest into T. But A’s MBO should not contain the final measurable outcome of A’s work, but A’s passion at attacking this unknown topic, right?